Once at the heart of their local communities, all nine of these pubs were lost to erosion in the 1900s. Many were photographed in the ‘Golden Age’ of picture postcards before the First World War – some in their heyday, others in the months before they were lost. Of course, the most striking photographs are when they teeter on the brink, not least an abandoned Lord Nelson at the edge of a crumbling English cliff.

1. The Royal Oak, Isle of Sheppey, Kent

By my 1970s childhood, the Royal Oak stood derelict on Minster cliffs and was known as the Pub With No Beer. In the 1940s and 50s my nan played piano there, and I remember the ruined piano still in the bar. Outside, in what remained of the beer garden, the doorless gents was just beginning its journey to the shore.

Originally an isolated farmhouse, the Oak had a reputation as a smuggler’s pub, and in the 1860s had ‘extensive pleasure gardens’ leading out towards the cliff. These had gone by the late 1950s, leaving the pub so close to the edge it was forced to close its doors. For some time afterwards, a sign stood outside. ‘Sorry,’ it said, ‘this aint a pub no more’.

2. The Lord Nelson, Pakefield, Suffolk

The Lord Nelson was one of several Pakefield pubs lost during a period of rapid erosion in the early 1900s. The photograph above shows the original pub at the brink of the cliff. By then, the publican had moved in next door, along with his licence. In both these photos, you can see his licencee board hung above the door, and in the one above also its ‘ghost’ in unpainted brickwork on the derelict Lord Nelson.

This new Lord Nelson, though, lasted only a matter of months. In the photograph above, taken later that year, the original pub has already fallen – along with the ground it stood on. Given how close this building is to the edge, and the speed of erosion in Pakefield at the time, it can’t have been long before this one went too.

3. Cliff Hotel, Pakefield, Suffolk

A couple of years later, on the other side of its shrinking village green, Pakefield also lost the Cliff Hotel. Built in 1875, it is shown on the right in the postcard above – with the photograph taken the same year the two Lord Nelsons crashed to the shore.

By 1905, crowds gathered daily at the end of Pakefield Street to watch the sea’s destruction of nearby houses and the Cliff Hotel. The landlord, though, is said to have continued serving ‘until the bitter end’.

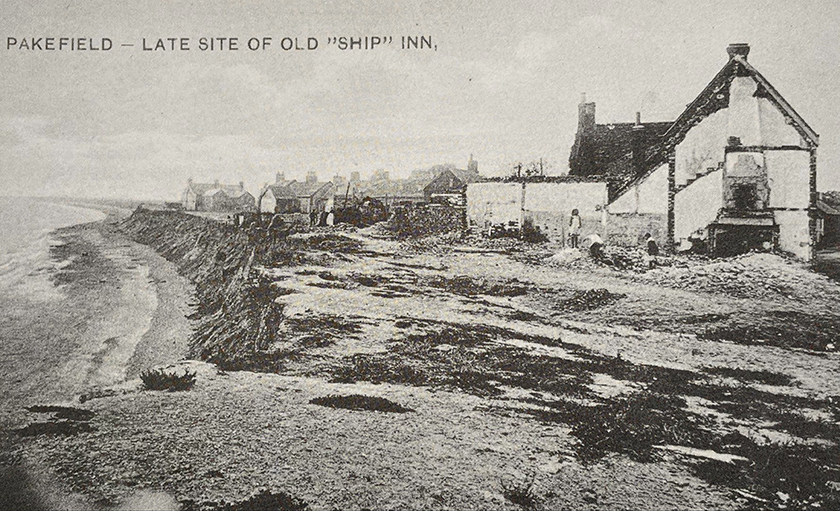

4. The Ship Inn, Pakefield, Suffok

The atmospheric photograph below shows the end of Pakefield Street after the loss of the Cliff Hotel. The old Ship Inn still stands on the right, with a woman in white in the doorway. Beyond the pub, houses and much of the one-acre Pakefield Green had already been lost to erosion. I’m told the original Ship Inn – like the Lord Nelson – was previously in the seaward building next door, with wood panelling and protruding sign.

Like other pubs here (the Royal Oak, Smack and Three Mariners at least), the Ship had a reputation for smuggling along with wrecking and salvage. As was common in the 18th and 19th centuries, the pub was home to the local ‘Beach Company’. Often groups of fishermen, they kept a lookout and were ready to head out to ships in distress – on this coast often wrecked, run aground or abandoned on sandbanks. With money to be made, rivalry between neighbouring beach companies was fierce, along with the men’s reputations. Yet company rules on a wooden board at the Ship included: ‘Whatever earnings shall be, thou shalt give to the aged and infirm a share’.

By 1910, the Ship’s licence had been transferred to new premises. Yet like many neighbouring properties, the original Ship Inn was largely dismantled as the cliff drew near, with materials salvaged for reuse elsewhere. Half-a-mile inland, the lobby of today’s Ship retains glass door panels from the original Ship Inn – etched with the old brewery’s anchor logo, RETAIL and SMOKE ROOM.

5. The London Inn, Hallsands, Devon

Until 1917, the village of Hallsands stood on a rocky platform at the foot of a South Devon cliff. In 1855, the writer Walter White came across ‘about a dozen rude little cottages, some close to the shingle… others on ledges and recesses of the cliff’. Doubting he’d find lodgings for the night, White spied ‘a swinging sign, ambitiously inscribed The London Inn‘.

After dredging began offshore in 1897, the pub and village suffered repeated storm damage. By 1904, no longer protected by its shingle beach, the London Inn was in ruins. ‘The roof came down on us,’ the landlord said. ‘It was with the greatest difficulty that we grasped things to prevent us falling into the surf… We had just got out the last of the furniture when the whole pile went like a pack of cards’.

During prolonged gales in 1917, the rest of the village was lost. Today, all that remains of the London Inn are a few grooves in the wind- and wave-worn rock.

6. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Blackpool

I describe Uncle Tom’s Cabin in more detail here, so will keep this short. Having started out as a ginger-beer stall in the 1850s, by the end of the century it included bars and tearooms, a dancehall and sideshows. The undefended cliff, though, was now encroaching by 4-8 feet a year. In 1901, the smoking room was the first to go over. After that, the bar moved further from the edge. But in October 1907, when more of its buildings collapsed during a storm, Blackpool’s first entertainment venue was forced to close its doors.

7. The Lifeboat Inn, Spurn, Yorkshire

Out on Spurn at the mouth of the Humber, the Life Boat Inn above was not the first to be lost to the sea. With the lifeboat crew stationed on the spit from 1810, its predecessor was little more than a room in the coxwain’s cottage. Describing a visit in the 1850s, one traveller wrote, ‘There was once a garden between it and the sea; now the spray dashes into the house; for the wall and one-half of the hindmost room have disappeared along with the garden’.

Later, a replacement two-storey Life Boat Inn was inserted into the row of coastguard cottages. The photograph above shows the pub mid-row, and home to the family of James Hopper: landlord from the late 1870s for more than 30 years. By the First World War, repeated flooding meant the cottages seaward of the pub were pulled down. This left the Lifeboat Inn at the end of the row, jutting out on a chalk-defended promontory.

Although closed as a pub by the 1920s, the building was still standing in 1953, when Spurn was hit by the devastating North Sea storm surge. In a photograph of the aftermath, the force of the water has swept away the old pub’s gable end, exposing the rooms like a doll’s house. Unlikely as it seems, the building was repaired and protruded out into the Humber for another 25 years, until it was demolished along with the cottages. Today, out on remote, uninhabited Spurn, high tides lap its concrete foundations.

8. The Three Mariners Inn, Slaughden, Suffolk

The Three Mariners, along with the rest of the village of Slaughden, was abandoned to the North Sea by the 1930s. A seamen’s pub on the site of the fifteenth-century Anchor inn, its low-ceilinged snug overlooked Slaughden’s once-thriving fishing and ship-building quay. Above the door hung a striking pub sign, on whalebone brought back from Icelandic waters by local fishermen.

Out on a shingle spit with its back to the sea, the Three Mariners had long been at risk of flooding during gales and surges. Following a series of storms in 1895, the Ipswich Journal described the bar half-filled with sand and shingle, the tables smashed and beer barrels flung by the waves. The landlady and her children had to be rescued by boat.

The last baby born in Slaughden was the boat-builder’s son, Ron Ashton. At the age of 86, Ron described how his family were washed out of their home for the fifth and final time in 1926, during a storm that piled shingle almost to the second floor. Within a decade, what remained of the village was abandoned. Finally, the 1953 North Sea surge swept away the last of Slaughden’s boatsheds, and buried its ruined cottages and the pub in shingle.

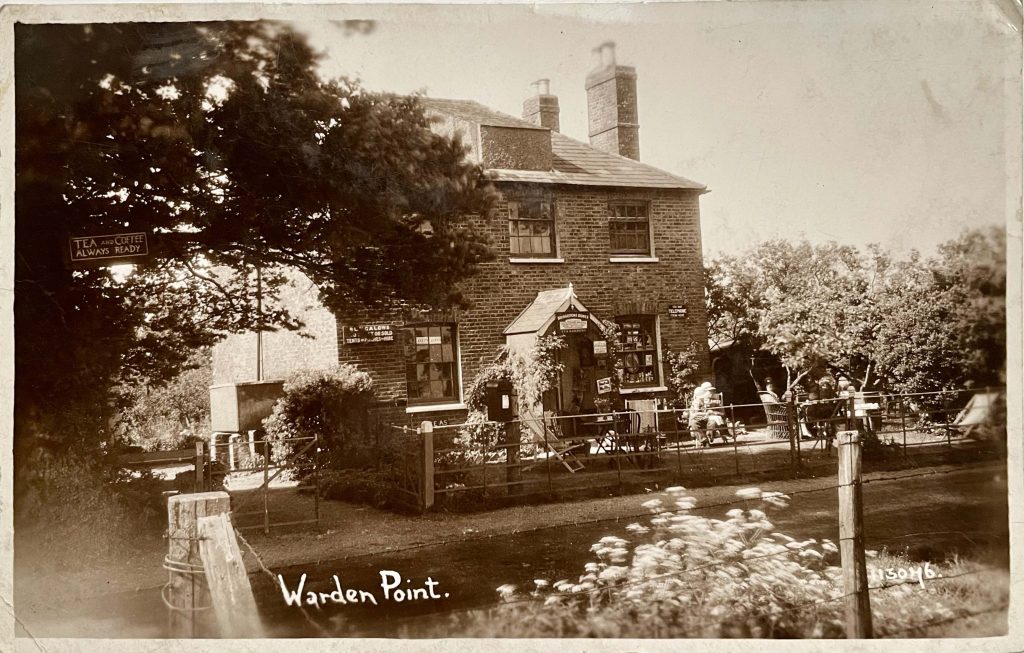

9. The Smack Inn, Isle of Sheppey, Kent

As in the postcard above, this last pub ended its days as Bridgestone Stores, tearoom and Post Office. Bought and closed as a pub by a rival publican, it was previously the Smack Inn. Like the Royal Oak – the Pub With No Beer – it stood a few miles along the cliff from where I grew up. Out in an isolated spot on the Isle of Sheppey, the Smack is said to have been used by smugglers with the notorious North Kent Gang (although court reports from the 1850s show mainly successive Smack landlords fined for opening on Sundays during divine services).

In 1971, a major landslide undermined nearby cottages and took their gardens (there is more on Warden’s landslides here). It also left the ex-pub sixty feet from the edge of the cliff. Having only bought Bridgestone Stores a month earlier, Sid Smith and his wife saw their walls crack and the floorboards open up. Left derelict for years, and later demolished, the last of the old Smack slipped quietly over the cliff in the late 2010s.