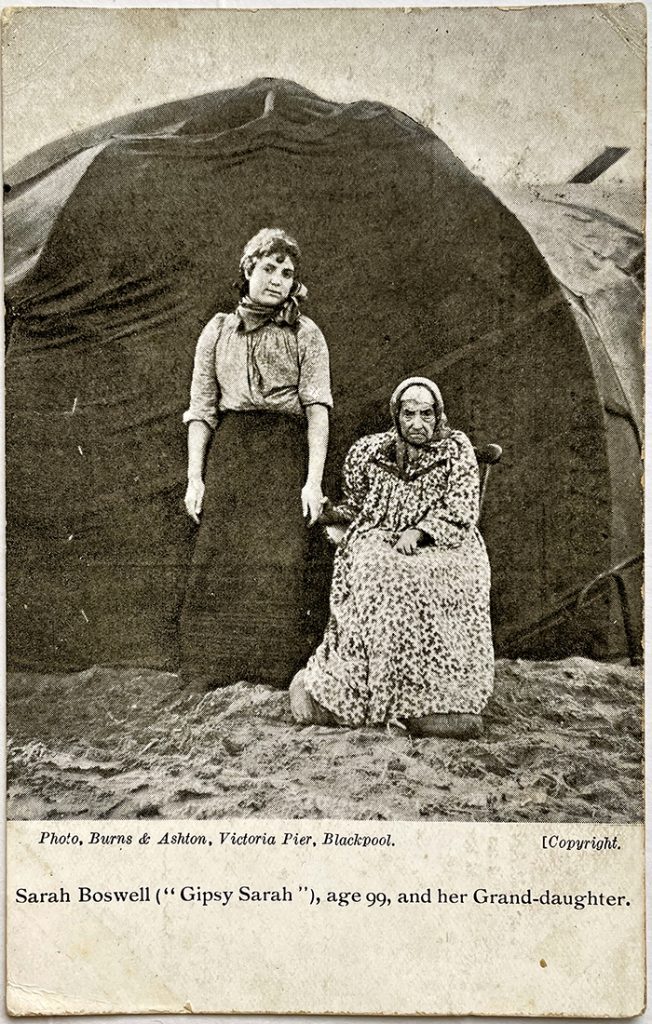

Until it began to collapse into the sea, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was Blackpool’s first entertainment venue. It started out in the 1850s as a ginger beer stall selling sweets and nuts, with fortunes told by ‘Gipsy Sarah’. With a traveller encampment on nearby cliffs since the 1830s, Sarah’s husband Ned was among the first to settle there.

The arrival of the railway in 1846 brought mass tourism to Blackpool. With cheaper, easier travel came trippers and the Wakes Week crowds, as factories closed down and entire neighbourhoods decamped for a week by the sea.

Keeping pace with the influx, Uncle Tom’s Cabin expanded into a growing collection of huts and wooden buildings on the clifftop. From a ginger beer kiosk, it evolved into a popular bar, dancehall and tearooms, with sideshows and musicians alongside the palmistry.

‘No lawns, gardens or bowling green,’ commented one visitor in the 1870s. ‘Is it because there is no sense of permanence with the sea encroaching year by year?’

As business in Blackpool boomed, the Romany travellers were moved on from the North Shore cliffs. Joining others already on the South Shore, they pitched their tents and fortune-telling booths out on Blackpool’s sands. By the 1901 census, Sarah Boswell is described as head of the family at 96 years old, ‘living on own means’ at ‘Gipsy Encampment, Sandhills’.

By then, Uncle Tom’s Cabin teetered at the edge of the cliff. On the shore below, much of the shingle had been removed as ballast for the railways. And with the foot of the cliff exposed to storm waves, the sea was now encroaching by four to eight feet a year. In 1901, the smoking room was the first to go over.

After that, the bar was moved back from the cliff and recreated in a ‘Wild West style’. For a while, with more than three million visitors descending on Blackpool each year, Uncle Tom’s continued to thrive. But in October 1907, when more of its buildings collapsed during a storm, the town’s first entertainment venue was forced to close its doors.

Unrecognisible today, Blackpool’s northern cliffs are defended by a vast concrete sea wall. Yet stories of an inn lost to the sea live on, with ghostly laughter said to drift ashore from drunken revellers at the Penny O’Pint.