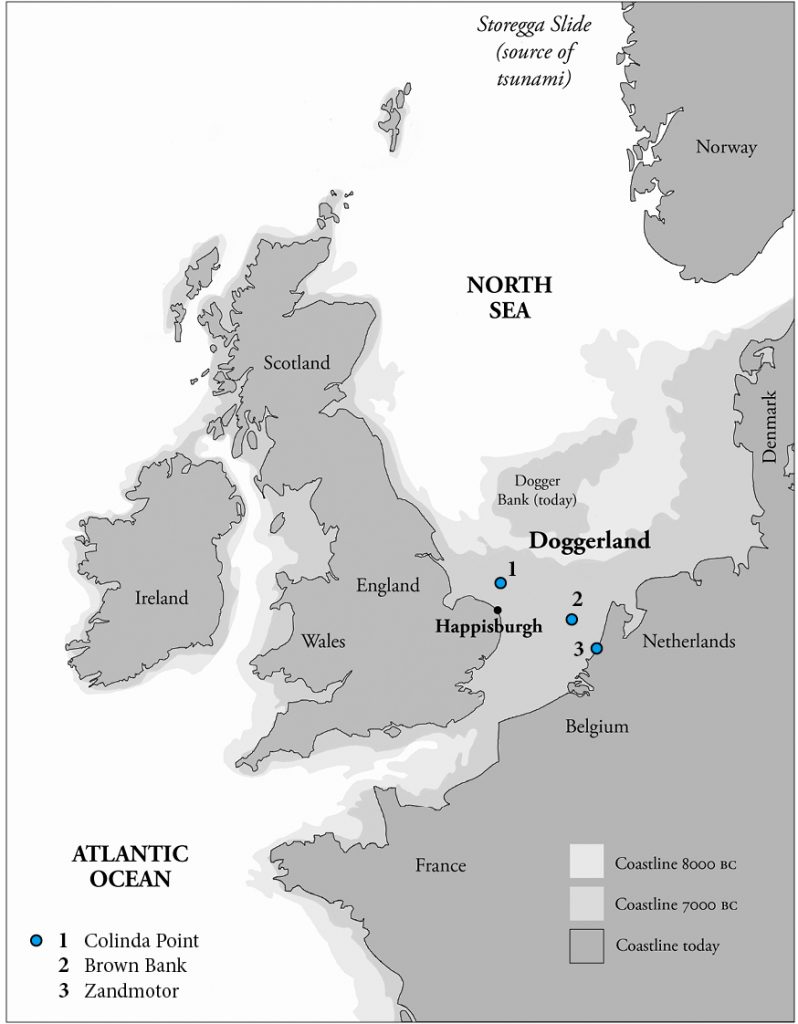

As I’d been reading a lot about Doggerland, pocketing my first moorlog ‘pebble’ in Norfolk was something of a thrill. A vast drowned landscape beneath the North Sea, Doggerland was first named in 1998 by the archaeologist Bryony Coles, after the Dogger Bank. The sandbank, in turn, took its name from the traditional Dutch fishing boats – dogges – that worked its rich, shallow waters.

Until then, this submerged landscape was seen as little more than a landbridge that connected Britain to Europe when sea levels were lower. Yet more recent research suggests that by the mid Mesolithic, Doggerland had the richest hunting and fishing grounds in North-west Europe.

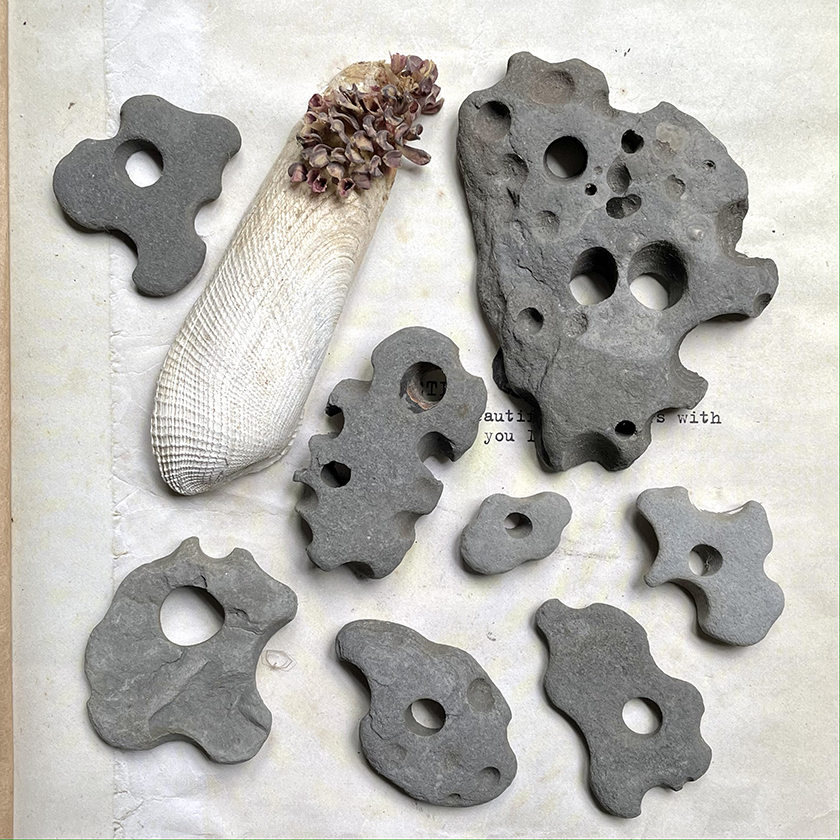

Smooth, dark and still damp, those first moorlog pebbles were left low on Happisburgh’s foreshore by an early tide. Others I found later were high on a storm-beach in the sun. Over weeks and months, they’d dried out to reveal the fibrous texture of peat, with all its clues to their origins on the North Sea floor.

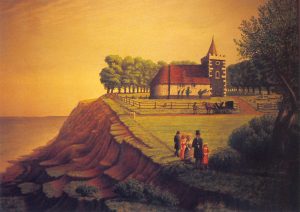

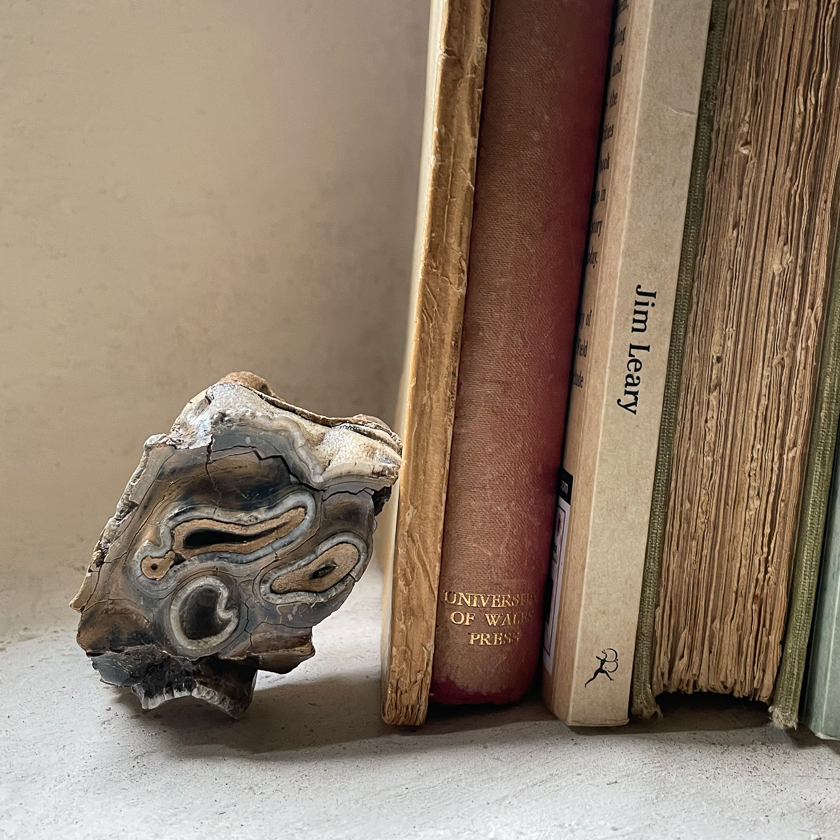

Spotting the fragment above, I thought grizzled shoe-sole before I saw moorlog. Dusted with salt crystals, the peat was pierced with finger-sized holes, that I recognised – with glee – were made by piddocks. Usually, these elegant marine bivalves live embedded in soft seabed rock such as chalk or slate. Yet here they’d burrowed into an ancient fen beneath the sea.

More than a century ago, the geologist Clement Reid studied moorlog for his groundbreaking book Submerged Forests (1913). He described how for the past fifty years, Norfolk fishermen had been trawling up moorlog as by-catch in the middle of the North Sea. Usually, like the occasional weighty mammoth bone, they just threw it back overboard.

But Reid took some of the moorlog home, where he and his wife boiled it in the kitchen for days. After sieving the remains, he identified mainly ‘swamp-species’ such as mosses and willow, hazel and seeds of the bog-bean. Finding no brackish species, he concluded the moorlog had eroded from what was once ‘the middle of a vast fen’.

The first trace of humans in Doggerland was found two decades later in 1931, in a chunk of moorlog trawled up 25 miles off the Norfolk coast. Before throwing it back, one fisherman broke it up with a shovel – and hit something hard.

Inside was the beautifully preserved barbed point shown above. Carved from the antler of a red deer, it became known as the Colinda Point (after the fishing boat) and would have been used as a spear or harpoon. Later, the point was radiocarbon dated to 14,000 years old.

(Photos: National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, Netherlands)

In the decades since, some extraordinary artefacts have been trawled and dredged from the North Sea floor. Entombed in peat and buried for millennia in sediment, many are strikingly well preserved. From Neanderthals to the last Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, it is a precious glimpse of life in Doggerland before 6200 BC – when its last hills slipped beneath the sea.

(Photo: Paul Storm, University of Groningen, Netherlands)

Other traces have been found by beachcombers, particularly since the rise of ‘sandscaping’ projects to defend against out own rising seas. The first experimental scheme, in the Netherlands near the Hague, is known as the Zandmotor or ‘Sand Engine’. By 2011, millions of tonnes of sand had been sprayed on the existing beach, to protect low-lying coastal towns.

(SOURCE)

By chance, the sand was dredged from an area of Doggerland once occupied by humans. So along with sand, the Dutch beach was sprayed with ancient bones and artefacts. Inevitably, as word spread, the Zandmotor became a magnet for beachcombers, archaeologists and fossil hunters.

Among the most common finds were more than 2000 Mesolithic barbed points, carved – like the Colinda – from antler and bone (mainly deer but sometimes human). Other Zandmotor finds include the teeth and tusks of mammoths, bone fish-hooks and arrowheads, bison and aurochs bone, handaxes and fragments of Mesolithic human skulls.

More recently, similar sandscaping projects in Norfolk and Essex have also sprayed local beaches with Neanderthal stone tools from miles offshore.

Back in Norfolk, I stowed my precious moorlog in bags beneath the van’s seats. But then completely forgot they were there. Several weeks later the moorlog turned up, as – fearing a leaky roof or worse – I searched the van warily for the source of an earthy smell of decay.