Researching tales of enchanted islands off the west coast of Ireland, I came across some fantastical images. The roots of the stories lie in medieval legends of seafaring Irish monks, including the ninth-century Voyage of Saint Brendan and even earlier Voyage of Bran.

In search of the Otherworld, Bran and the monks set out in a currach, a hide-covered row-boat. Two days out into the Atlantic they meet Manannán mac Lir, Son of the Sea, and ruler of Land Under the Wave. From a magical horse-drawn chariot, he directs them to the Land of Joy (where one monk is left ‘laughing and gaping’) and the Isle of Women.

The later Voyage of Saint Brendan recounts the travels of sixth-century Brendan of Clonfert and another group of Irish monks. Setting sail from Kerry in search of the Promised Land, they reach islands that epitomise salvation or damnation. There is an Island of Sheep and a Paradise of Birds, an island with choirs and grapes the size of apples. But some monks drink too much water from a well and sleep for days. Blacksmiths pelt them with foul-smelling slag. They are attacked by a gryphon, their boat is encircled by threatening fish, and demons take one monk to Hell.

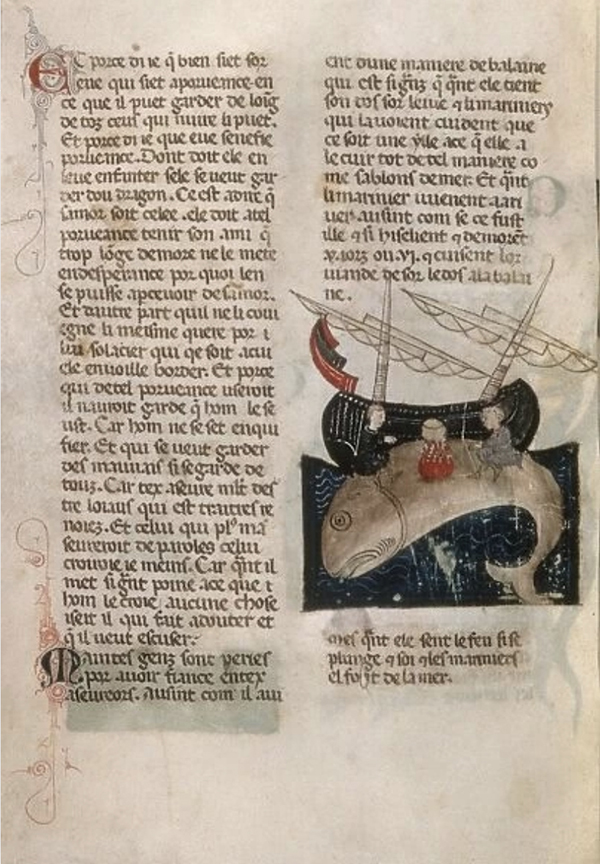

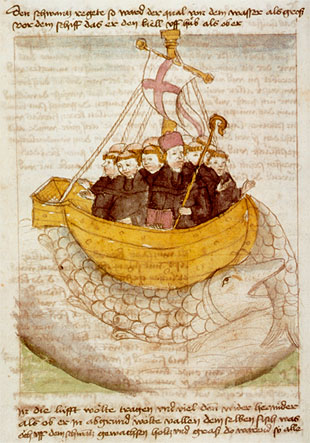

A common scene from the manuscripts shows the sea monster Jasconius. Mistaking the sleeping whale for an island, the monks land and build a campfire from driftwood, which wakes Jasconius. Yet the whale proves benign, and for the next six years returns each Easter for the monks to celebrate mass on its back.

In ninth-century Latin, the original Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (Voyage of St Brendan the Abbot) was translated first into Irish and then back into Latin. From there, it went on to become something of a European bestseller. Copied and re-copied through the centuries, the tale was translated into German, Flemish, Italian, Catalan and Norse – even Anglo-Saxon rhyming couplets.

Of course, I needed no encouragement to head off down internet rabbit-holes in search of illuminated manuscripts showing campfires on the backs of whales.

In one twelfth-century Dutch translation of the Navigatio, St Brendan and the monks encounter people with swine heads, dog legs and wolf teeth. Later, they find Judas Iscariot mid-Atlantic on a barren rock, frozen on one side and burning on the other.

The Anglo-Norman version, written in rhyming couplets around 1121, dwells on this scene in detail. As the monks draw near to his wave-lashed rock, a flayed, half-burned and half-frozen Judas describes how he is tortured differently each day of the week. On Wednesdays, for instance, he is boiled in pitch and forced to drink molten metal, whereas on Fridays he is skinned alive and rolled in soot and salt.

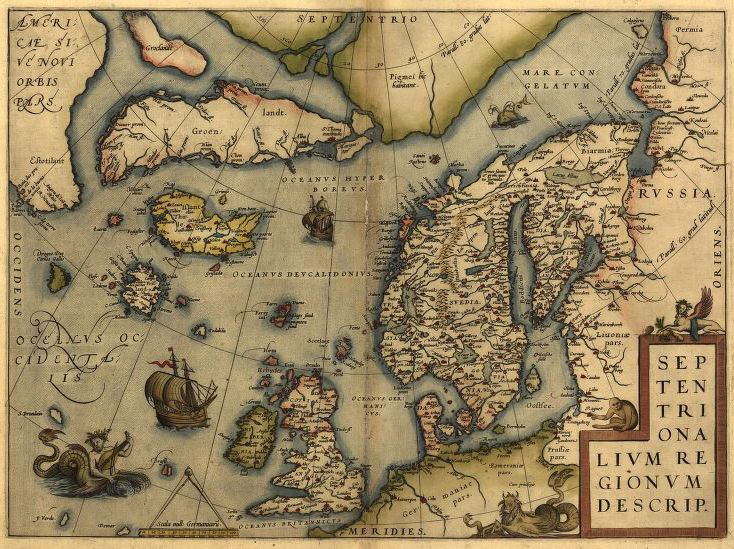

Eventually, after a seven-year voyage, Brendan and the monks reach the Promised Land of the Saints. For centuries after the story became popular, a St Brendan’s Isle appeared mid-Atlantic on maps and charts. It is also marked on the Erdapfel, the world’s oldest globe. Completed a year before Columbus’s return in 1493, the globe doesn’t yet include the Americas – but clearly shows a St Brendan’s Isle.

This leads some to suggest that medieval Irish mariners – if not Brendan of Clonfert – may actually have reached America.

Saint Brendan’s Isle is shown bottom left, above a violin-playing merman