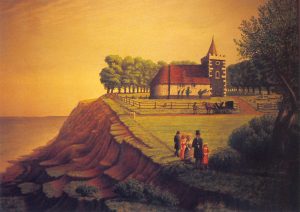

This postcard shows some wonderfully spectral Edwardians wandering the clifftop graveyard of St Michael and All Angels Church at Sidestrand. In the early 1880s, as the cliff edge drew nearer, its medieval nave and chancel were dismantled and rebuilt inland. The churchyard and tower, though, were left on the cliff. And by the end of the century, it was known as The Garden of Sleep, after a poem by visiting London theatre critic Clement Scott.

In my garden of sleep,

where red poppies are spread,

I wait for the living, along with the dead!

For a tower in ruins stands guard o’er the deep,

At whose feet are green graves of dear women asleep

By 1905, the Sidestrand tower stood seven feet from the edge of the cliff. In 1915 cracks opened up in the circular walls, and a year later the tower crashed to the shore.

Over the centuries, Norfolk has lost many villages to the sea. Among them are Clare and Shipden, Foulness, Whimpwell, Eccles and Ness – with their rough locations marked on the map below.

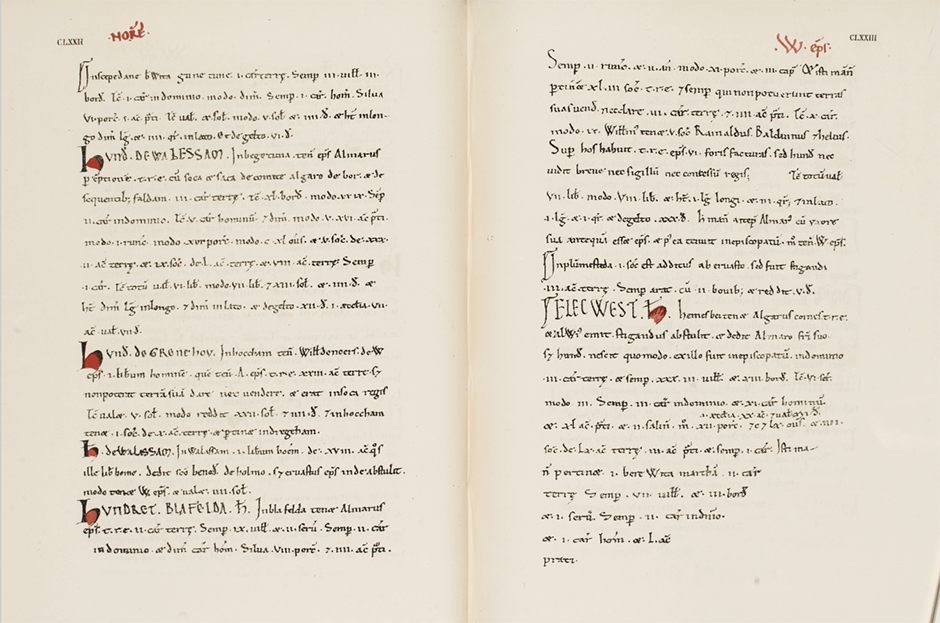

In 1086, Shipden was recorded in Domesday as having seventeen households, four-and-a-half plough teams, meadows and woodland for 36 swine. At its height, the village also had a manor house, harbour and Friday market, along with a church dedicated to St Peter, the patron saint of fishermen.

Records suggest most of Shipden, including its church, had been lost to the sea by the fifteenth century. Many residents are thought to have moved inland to what would later become Cromer. Inevitably, stories of the drowned village lived on. After its loss, the poor and opportunistic are said to have slept on the shore at Sidestrand, diving down at low tide to salvage remains from Shipden.

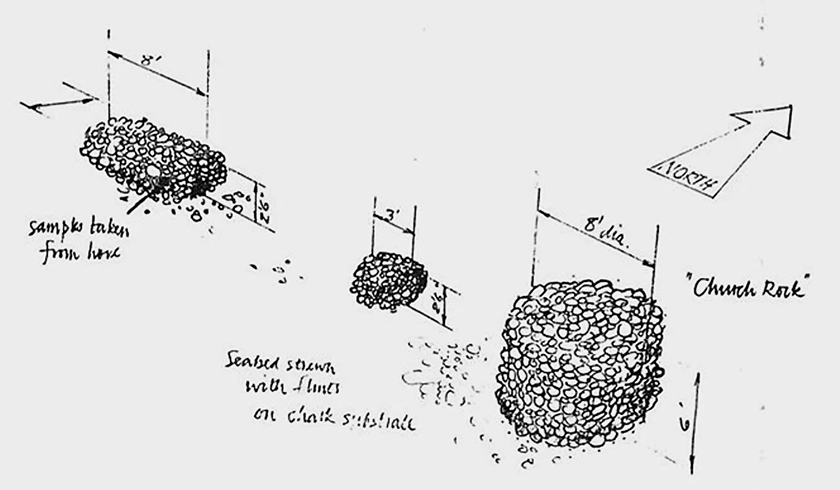

Rising some twenty feet from the seabed, a stone ruin remained visible at low tide into the nineteenth century. About 150 yards east of Cromer Pier, and marked on charts as a hazard to shipping, it was known to the fishermen as Church Rock (of course, local stories also told of church bells that toll beneath the sea).

With the arrival of the railway, the village of Cromer had grown into a tourist resort by the 1880s. Paddle-steamers now stopped offshore bringing day-trippers to be rowed ashore to Cromer’s jetty. At the height of summer 1888, though, one steamer ran aground on Church Rock. Holed, and with a hundred passengers on board, the SS Victoria stuck fast. Although all were rescued, the wreck remained a danger to shipping and was later cleared with dynamite.

Through the last half-century, many divers have finned down to explore what remained of the wreck and Church Rock. Following a series of dives in the 1970s, one Yarmouth Sub-Aqua Club member described ‘swimming along a street in Shipden forty feet below the sea, where people had once walked’. Other divers recalled ‘the ruined walls and doorway of a church, and the footings of houses along a road’.

In 1986, so he could see the ruins for himself, the former curator of Cromer Museum – Martin Warren – began dive lessons at a swimming pool with a local lifeboatman. That September, in murky darkness 23 feet beneath the surface, they found the sea floor littered with fragments of the old steamer as well as beach flints set in mortar. Along with cobbles from Shipden, they returned to shore with stone tracery from a church-like window.

Later, local mechanic and naturalist Percy Trett described another Church Rock dive in more idyllic ‘Mediterranean’ conditions. This time, underwater visibilty was close to 30 feet – rare in the silty, often rough North Sea.

‘The substantial remains of the flint walls,’ wrote Trett ‘were a colourful mass of sea anemones and soft coral, appropriately known as dead-men’s fingers.’ Out beyond the end of the pier, the ruined walls of old Shipden now offered shelter to hundreds of small Cromer crabs.

Another Norfolk church tower now lost to the sea (Photos Norfolk County Council)