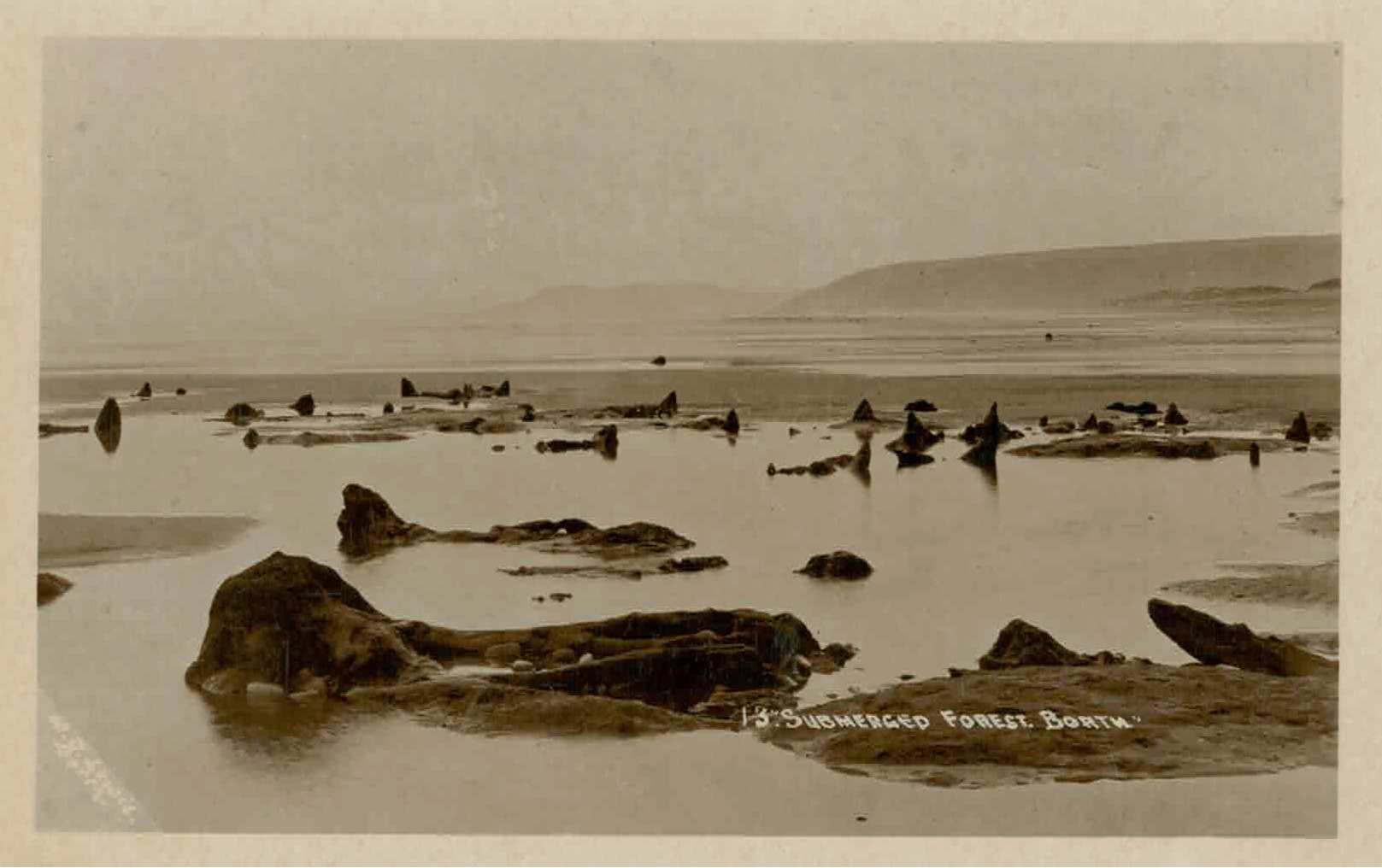

Borth was the first place I visited while researching Lost to the Sea. For most of the time, its spectacular submerged forest lies hidden beneath foreshore sand. Having no idea if it would appear before I finished the book, I was delighted to hear the trees were exposed – although afraid that by the time I got to Wales they’d be gone.

Reaching Borth at high tide, I still wasn’t sure until the sea slipped low enough that taller stumps began to break the surface.

My fascination with submerged forests began in 2014, when a series of scouring storms exposed prehistoric trees on a local beach. So much sand was dragged offshore that winter, it revealed remnants of submerged forests not seen for decades in Cornwall. All around Britain and Ireland, similarly ancient trees appeared off Atlantic, Irish Sea, Channel and North Sea shores.

Radiocarbon dating shows many of the trees died 4000-6000 years ago as sea levels rose – although the forest at Borth is by far the most striking and extensive.

Here, the stumps and fallen trunks of hundreds of birch, oak and hazel trees remain embedded in peat that’s preserved them for millennia. Stretching off into the distance towards Ynyslas, the stumps are spaced much as they would have been some 4500 years ago, when sunlight filtered down through their leaves to the forest floor.

Now the trees stand, incongruously, in the sea.

Known once as Noah’s woods or Noah’s trees, these submerged forests were long thought to be remnants of the Biblical flood.

‘A very remarkable circumstance occurred’ wrote Gerald of Wales in 1188, ‘the trunks of trees standing in the very sea itself… like a grove cut down, perhaps at the time of the deluge, or not long after.’

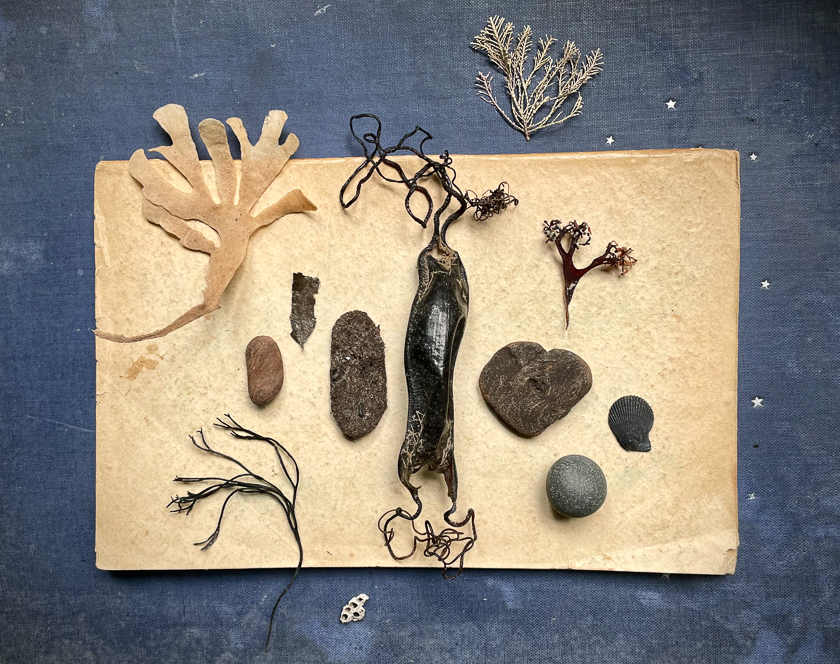

Below: the splayed roots common in trees that have grown in waterlogged fen woods

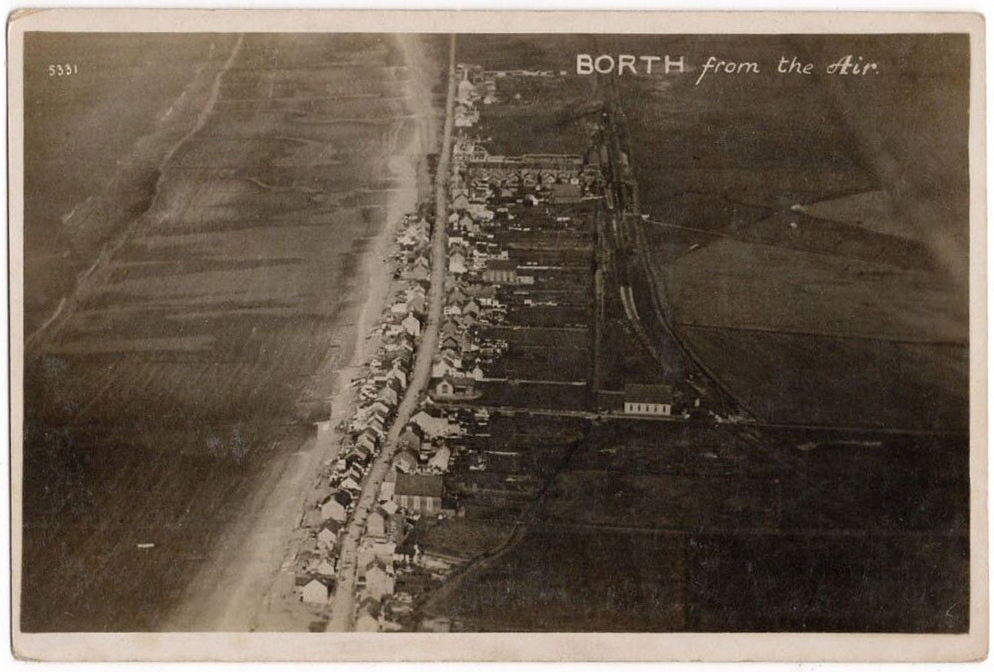

Of course, storm waves that uncover the forest also put low-lying Borth at risk. The vulnerability of this seafront village is clear in the aerial photograph below, taken in summer with the forest buried, as usual, in sand.

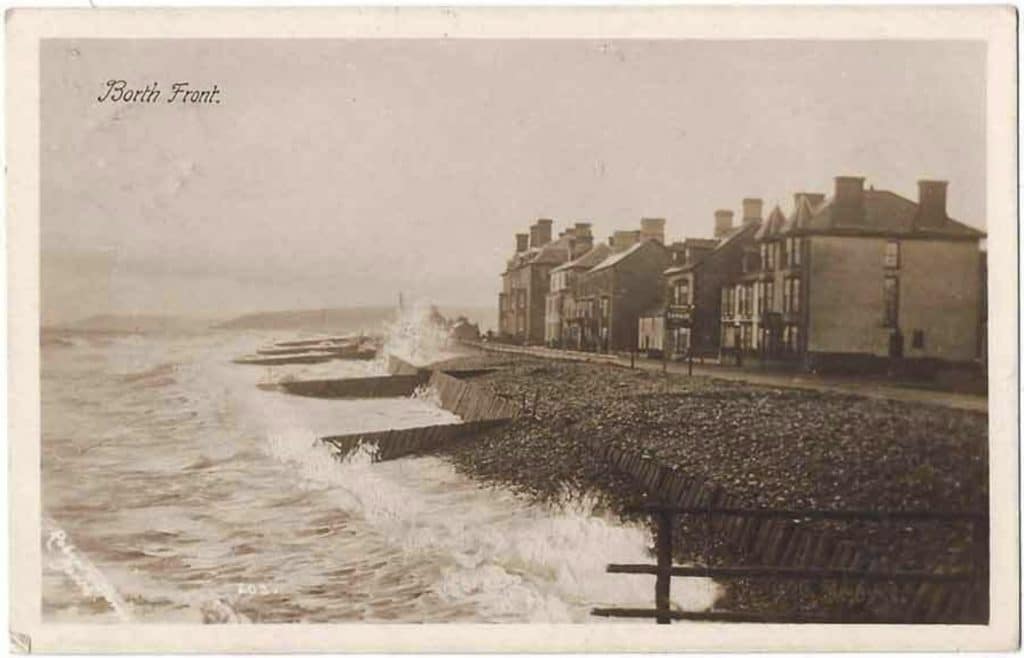

Most destructive are south-westerly gales, which drive Atlantic waves straight through the channel between Ireland and Wales to the shore at Borth.

One of the worst peaked on a Wednesday morning in October 1896, as hurricane-force winds coincided with high spring tides. Local reporters described waves rushing through seafront houses, bursting through front doors to sweep furniture and clothes into the street.

Three days later, Borth was in ‘a pitiable condition’: smashed windows, downstairs rooms filled with tons of shingle and stone, collapsed walls and upper stories resting on props. The wind was ‘causing the water to run in waves from field to field and from garden to garden, which left the houses between two waters, and in a highly dangerous position.’

For now, the Shoreline Management Plan for Borth is ‘Hold the Line’. Since 2011, the village has been protected by banks of imported grey pebbles – rather than the old adverts’ four miles of golden sand. Beyond the stones, great boulders shipped from Norway form a series of massive breakwaters and offshore reefs, causing waves to break before they reach shore.

Inevitably, this has changed the dynamics of both the beach and foreshore, with locals describing how the forest now appears more often but vanishes more quickly. For me, it was a deeply evocative place, and the preservation of the trees uncanny.

So if you’re curious and hear the forest is exposed, I’d say get there while you can (or google ‘bog bodies’ and visit a museum).