‘Having crossed London on the Tube wearing wellies (which always gets a few glances), I walked into Wapping through cavernous streets overshadowed by luxury warehouse conversions. When I reached the alley leading through to Wapping Old Stairs it was sunk in shadow, slicing between buildings to a strip of sunlit shore.’

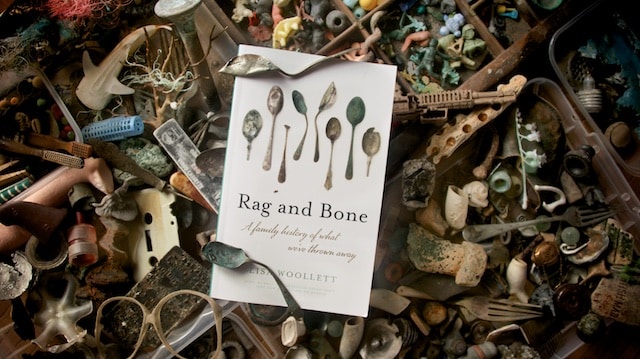

From ‘Rag and Bone’

I found some of the coral and the money cowrie (below) near Wapping Old Stairs, although neither species is native to the mud of the Thames. Thriving in clear, tropical waters, they were probably dumped amongst ballast from merchant sailing ships around the 17th and 18th centuries, when Wapping was at the heart of the British Empire’s maritime trade.

Money cowries were also imported in vast quantities from islands in the Indian Ocean, as they were used as currency in Africa. Shipped out from London on a first leg of the triangular routes of the slave trade, on arrival in Africa the shells would be exchanged for gold, ivory and slaves. By the mid 1700s, one enslaved African could be bought for 25,000 cowrie shells.

In a notoriously cruel ‘middle passage’ between Africa and the Caribbean, the shackled slaves were crammed into holds in such appalling conditions that up to one in five died at sea. Of those who did survive, many were then put to work on English sugar plantations, as this ‘white gold’ had become Britain’s most valuable commodity.

I found this plain terracotta ring on the Thames foreshore and for some time had no idea what it was (my first thought was that it might be a medieval ‘bunghole’, which prompted a fairly disconcerting Google image search). Months later, the Finds Liaison Officer at the Museum of London took one look and said it was the drain hole from a 17th century ‘sugar mould’, describing their tall, conical shape in the air.

Arriving in London on the final leg of a slave ship’s journey, the raw Caribbean sugar would be unloaded at one of the city’s riverside refineries. There, the hot brown sugar – mixed with clay, charcoal and sometimes blood – was drained through these conical moulds resting in collecting jars (the syrupy molasses dripping through was known as the ‘bastard’, and was used to make a darker, inferior sugar).

Once hardened, the white sugar was tapped free as a cone-shaped ‘sugarloaf’, which is how it was sold in the shops. Broken up with a hammer or ‘sugar axe’, it was then cut into smaller, more manageable pieces using tong-like ‘sugar-nips’.

Back in the 17th century, when the bastard was draining through my terracotta find, that refined white sugar was so expensive it was shown off as a luxury in wealthy homes.

.

There is more on the ‘Travelling Museum of Finds’ here

and reviews of Rag and Bone (John Murray, July 2020) here