In the past, goose barnacles attached to mainly driftwood. Now though, I find them on everything from plastic bottles, fishing gear and toothbrushes to disposable lighters and flip flops.

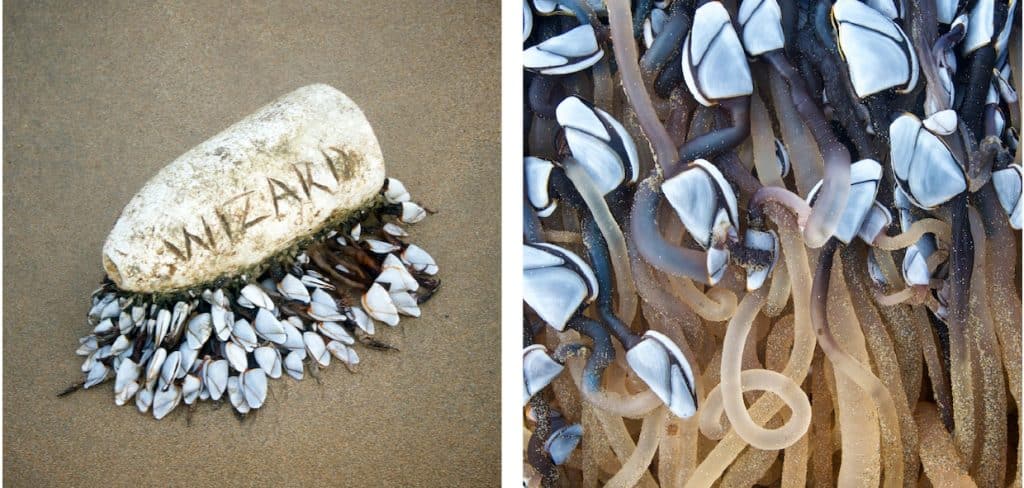

As larvae, goose barnacles drift in the plankton until they chance on flotsam. If they do, they then cement themselves on and begin to mature, growing shells at the end of rubbery ‘goose-necks’.

Unlikely as it seems today, in medieval times the goose barnacle was thought to be the embryonic form of the barnacle goose (when the barnacle’s feeding limbs are extended, they look a little like feathers). As barnacle geese leave Britain to breed, no one here had ever seen their eggs. The myth persisted, long after it might otherwise have done, as it meant the barnacle goose was considered fish and not meat, so could be eaten during Lent.

Another species, the buoy barnacle (below), secretes its own airy cement ‘buoy’ that allows it to float at the water’s surface. In his 1851 monograph on the barnacle, Darwin devoted eight detailed pages to their anatomy, describing the buoy as a ‘beautiful and unique contrivance’.

Looking rather like a bead of expanding foam, the buoy is often attached to flotsam as well. This can be almost anything that floats, including cuttlebones, plastic bottle tops (above), even the tar balls that result from oil spills.

The one above was amongst several that washed ashore attached to feathers. I was with my children and initially we thought they were dead, until they laid one on the surface of a rockpool. The moment the it touched water, the translucent plates opened and feathery limbs emerged, unfurling to sweep the water for food.

With plastic so long-lasting, goose barnacles have sometimes travelled vast distances, with their size a clue to how long something has been adrift. The mature colony above washed up in North Cornwall after a storm, and as the buoy had the boat’s name cut into its hard polystyrene I was able to trace its journey. Eight years earlier it had been lost from a lobster boat south of New York, so had traveled some 3000 miles across the Atlantic.

The buoy above was almost entirely covered with acorn barnacles. On closer inspection there were also keelworm tubes, bryozoans and finger-nail sized oysters. No doubt it was also colonised by the microscopic bacteria, biofilms and pit-formers of what scientists describe as the ‘plastisphere’. This newest of ecosystems is another way we alter evolution.

.

There is more on the ‘Travelling Museum of Finds’ here

and reviews of Rag and Bone (John Murray, June 2020) here