‘We headed towards Warden Point – which is no longer a point – and the strange, unstable landscape felt almost immediately remote. On exposure to air, London clay weathers to brown, and here it rose above the shore in odd peaks and turrets. In places a crumbling, teetering pinnacle was held together by no more than the remains of a single scrubby bush, its exposed roots curling out into the air.’

From ‘Rag and Bone’

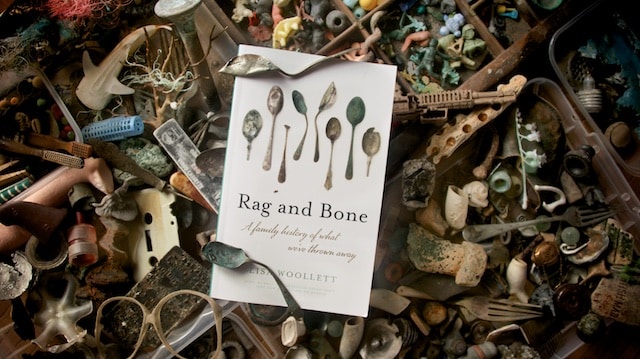

I grew up near these cliffs on the Isle of Sheppey, where the erosion has created an extraordinary foreshore. For as long as I can remember it has been strewn with wave-worn treasure and fly-tipped junk, which is washed from the toe of the cliff during storms and high tides. The way the soft clay slumps means everything washes out together, from sharks’ teeth and 50 million-year-old fossils to 1950s Bakelite and bulky 1980s video recorders.

Occasionally light bulbs erode from the clay, or more often just their screw and bayonet fittings. It was finding one that set me off on a trail of research for Rag and Bone, where I learned of their connection to the ‘Phoebus cartel’. Established in the 1920s, this is the best-known early example of planned obsolescence (reducing the lifespan of a product, in this case through making parts of lower quality).

Evidence for the cartel only emerged decades later, when leaked documents showed a worldwide group of major light bulb manufacturers – including Phillips, General Electric and Osram – had colluded to make their bulbs more fragile, so they would burn out faster. Whereas in 1924 the industry standard for a bulb was 2,500 hours, by the 1940s they had it down to 1,000 hours.

As the tide grades its trash and its treasure by density, I often find metal – like the light bulb fittings – amongst the dark drifts of pyrites that wash from the cliff (including fossil twigs, molluscs and palm fruits). Sometimes the things I pick up are immediately familiar. Yet others remain a mystery, if only until that first sweet moment of recognition – and perhaps nostalgia. A single tine from a fork maybe, a ‘spam key’ or the buckle of a snake belt.

I loved the element of chance that random finds brought to the book. It grew slowly, as new-found objects sent me off on unexpected trails of research, forming connections I hadn’t previously considered. Equally, my reading influenced the places I visited and the things I hoped to find (I was equally delighted with fragments of bone comb and wave-worn plastic dinosaurs). As I picked my way across the mud and stones, there was always that question: how might this object in particular be connected to a wider story of consumption and waste? For the light bulb, it was planned obsolescence.

.

More on the ‘Travelling Museum of Finds’ here

and reviews of Rag and Bone (John Murray, June 2020) here